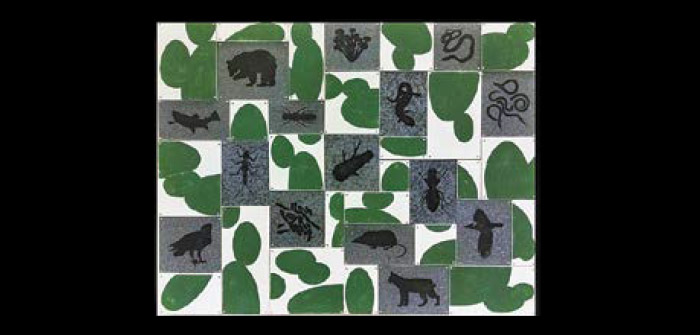

(Andrews Web. Wood, galvanized steel, silkscreen, acrylic paint, 36″ x 48″, 2016 by Andries Fourie)

Andries Fourie is an Oregon-based artist, curator and educator whose current mixed-media explorations of place and identity innovatively unite both formal and conceptual artistic concerns. Fourie comes from South Africa by way of French Huguenot ancestors who fled to the Netherlands during their persecution by the Catholics in late-1600’s France, and who were then sent to South Africa during the early colonization of the country by the Dutch. This rather complex and deeply informed explanation of his lineage is an apt metaphor for the artworks of Fourie that read as visual inventories of a puzzle-like nature to be deciphered by the attentive and inquisitive viewer.

Trained primarily as a sculptor, Fourie received a masters in art from California State University, Sacramento and a master of fine art from The University of California, Davis, uniting the former program’s strength in abstract, formal concerns with the latter’s focus on conceptual matters. The artist’s impressive exhibition record is complemented by the many distinguished positions he has held such as the U.S. Cultural Envoy to Namibia (2010), Associate Professor of Art (Sculpture) at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon (2012-2017), and Curator of Art and Community Engagement at The High Desert Museum in Bend (2017-2019). Despite these and other notable accomplishments, Fourie remains understated about himself and his work, simply explaining that for him making art serves as an important means to explore and understand the world.

In pursuit of this goal, Andries creates what he refers to as “the flattest sculptures ever,” two dimensional works that incorporate various materials affixed together on a single surface. Meaning permeates all aspects of his work, from that inherent in the materials themselves to the cumulative presence born of the various abstract and representational juxtapositions intentionally drawn together. With respect to the viewer, however, meaning often depends on both personal and cultural lenses. Knowing this, Fourie includes a multitude of signifiers in his works that can mean in a variety of ways for a variety of people. “I try to figure out how to make art function on multiple levels: a visual level, a symbolic level, an aesthetic level. The nature of art is non-linear, and I seek to make art accessible to more people by working across these multiple levels,” he explains.

In Andrews Web, for example, a fallen tree in black silhouette painted on an aluminum square panel provides the central point from which the web of life radiates outward. As suggested through the science-based illustrations, insects depend on nutrients from the fallen tree, small animals feed on the insects, and larger animals eat the smaller ones, a natural pattern identifiable to most. In near chessboard-like fashion, wooden, white rectangles containing green circular shapes alternate with the aluminum rectangles containing the black silhouettes of plants and animals seen in profile or from above, together generating an “every-other” rhythm to the piece, perhaps suggesting the rhythms of nature herself. The green (earth) circles suggest forms of attachment or relationship as smaller and larger ones connect via an area of overlap, an abstract representation of the interdependent systems necessary for life to exist and thrive.

“In some ways this work is a puzzle,” Andries explains. “I ask myself, ‘How do all these elements connect?’ When I made the work, I spent time with biologists, and they would say in broad strokes, ‘Here’s what’s going on.’ The idea of this web is really interesting to me and helps me to figure out how I can connect all these layers of animals to a log in a forest. The thesis is that when a tree dies, it spends a lot more time providing nutrients and having an influence on an ecosystem than it did when it was alive,” he offers (andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu).

The influence of science on art and, conversely, of art on science has been a longstanding one. From at least the time of da Vinci, the two have stood in mutual service, lending insights into one another’s theory and practice. Mark Dion is an American conceptual artist who Fourie cites as being particularly influential on his practice, specifically with respect to Dion’s use of scientific presentations in his installations. In Neukom Vivarium (2006), a seminal work by Dion, the artist creates an artificial life support system in the form of a greenhouse for a fallen Western hemlock, a permanent and interactive display in Seattle’s Olympic Sculpture Park. The installation speaks to the difficulty in recreating and sustaining natural systems once they’re gone, a topic about which Fourie is quite passionate. “I’m concerned about habitat loss and climate change, although my personality is not to be an activist in a direct way,” Andries reveals. Like Dion, Fourie uses art to make critical statements about the environment and the impact of human’s upon it.

Integrating the conceptual with the formal is a requisite of provocative, powerful, contemporary art. To complement Dion’s conceptual influence, Fourie looks to Charles Arnoldi, American painter, sculptor and printmaker, for inspiration regarding the formal language of painting. Having gained artistic acclaim in the 1970’s, Arnoldi has long been “fascinated with shape and pattern as they apply to advance formal concerns” (williamturnergallery.com/charles-arnoldi). In Arnoldi’s art, Fourie revels in the “pure joy of looking and experiencing color and form” and admires the ways he “breaks up an image that makes it a little bit like a puzzle” (Interview). “I’m drawn to abstract, modernist form,” Fourie explains, “but at the same time drawn to a more postmodern, conceptual content. Someone could easily say that’s a great flaw in my work, trying to simultaneously serve two masters that might be incompatible. However, I get really bored making my work if it is all ideas, and I don’t feel engaged or challenged if there isn’t a substantive visual part to what I do.”

Rather than a flaw, the integration of these two, fundamental artistic forces only strengthens Fourie’s art. In Summer Lake II, for example, the artist presents single silhouettes of birds that he inventoried at this south-central Oregon Wildlife Area with abstract shapes of a limited color palette. Together, the abstract and the representational create an intriguing pattern of warm and cool and light and dark, suggesting the cyclical nature of life. Avian silhouettes resonate with the black abstract forms, creating a strong visual connection, while the abstract shapes themselves appear as water droplets illustrating the basic resource that draws this complex of wildlife together. In Overlapping Elements in a System, Fourie creates an image similar to that of Summer Lake II, yet one distilled to its essential elements, forgoing any identifiable, representational forms.

As he seeks to explore and understand the world through art, Andries Fourie offers viewers the opportunity to pause and reflect not only on the web of relationships that permeate his works but also on the various forces and systems that shape our very lives, and reciprocally, the ways in which we influence these forces and systems through our own behavior. Fourie’s art is a persuasive nudge to exit the vacuum of our individual existence and experience and respect the interconnected nature of being.

To view the art of Andries Fourie, please visit his website, andriesfourie.com, or the Artists’ Gallery Sunriver where several of his works are displayed. For an interesting article on Mark Dion’s Neukom Vivarium, please read: art21.org/read/mark-dion-neukom-vivarium. To view examples of Charles Arnoldi’s art, please visit williamturnergallery.com/charles-arnoldi or lamodern.com/auctions/featured-artists/Charles/Arnoldi.