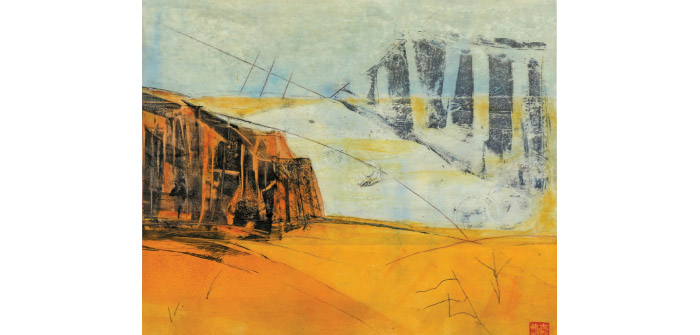

(Rimrock Fugue by Gin Laughery)

Gin Laughery’s landscape-inspired monotypes are strikingly beautiful in their vastness and seeming simplicity. With only a few carefully selected colors and their related tones, and a process both additive and subtractive and not exempt from chance, Gin pushes the medium to create deep and broad space, shifting the viewer’s focus between near and far, here and there. Time seems to unfold in hours and days as the eye travels as a hiker would, slowly and deliberately across the expansive terrain. A landscape unpeopled, the viewer is left alone to reflect upon its mystery, one evocative of a distant past and its ancient memories.

With such a powerful response to Laughery’s work, I was eager to know, “How does she create these feelings of mystery, intrigue and wonder?” Before addressing this question, Gin explains, via her website, what a monotype is and the process of making one: “A monotype is one-of-a-kind, a unique piece of artwork. It is the simplest form of printmaking, requiring only pigments, a surface on which to apply them, paper and some form of press. Monotypes are created by rolling, brushing, daubing or otherwise applying ink to a metal or plexiglass plate, and then ‘pulling’ the impression to paper or another form of canvas by use of a press. Monotypes are inherently unique because only one or two impressions may be pulled before the ink is completely removed from the plate… Each pulled impression may be considered a finished work, or may be further enhanced by the application of additional drawing or color.”

To explore her process in more specific terms, Gin agreed to speak about a couple of the particular prints chosen for this article. We begin with Forgotten Stories, a beautiful monotype composed of a burnt orange foreground that reads like a cliffside upon which pictographs are inscribed, a middle ground of sweeping, horizontal black lines evocative of rock outcroppings and distant mountains, and a background band of warm yellow sky. “When I walk through the landscape, I see remnants of earlier times like a rock that could have served as a tool for an ancestral hand or maybe something man-made like a piece of pipe,” Gin states. “I ask myself, ‘What was here before now? Who? What are their stories?’ I explore these questions in Forgotten Stories through a variety of subtle marks, indents in texture, and the soft curve of a hill to establish the rather abstract foreground. I then indicated something the viewer can relate to in the background: the suggested rock structures. I built many layers using semi-transparent oil-based ink to generate depth, a process that required many runs through the press.” In addition to building, there is also a subtractive component in Gin’s work as she scratches into or incises the topmost layer of pigment to reveal the color beneath it, delicately excavating the picture plane as an archaeologist would an ancient site. As if in the desert itself, eyes nearly shut due to its hot, high and dusty winds, Laughery says she seeks to portray “a landscape rid of the extraneous and keyed on the essential, seen as if squinting.”

In Rimrock Fugue, a print with a similar yet slightly cooler palette to Forgotten Stories, the artist divides the composition into three horizontal bands: a warm orange-yellow foreground with a few thin lines indicating a bit of grass or a tree, a middle ground composed of cool, light yellows and blues with an orange-black rock structure on the left, and a background of pale blue sky. The marks of the rock structure, presumably the rimrock, are vertical in orientation, providing a nice counterpoint to the otherwise horizontal composition. A similar formation, perhaps the inverse of the rimrock, made of dark, vertical, semi-transparent bands mysteriously hovers in the upper right, linking the middle ground and sky. Laughery explains Rimrock Fugue as follows: “I’m fascinated with rimrocks. For me, they are like elements in a musical fugue. For this print I used Japanese paper and put it atop a collagraph plate to get some embossing, which you can see in the circles in the far right middle plane. After the collagraph plate, I used a plexiglass plate and started with some black to represent the rimrock and then used a hotel card to scrap away pigment for a more suggestive feeling. I pressed wax paper into ink to create some finer lines and then incorporated water-based Sennelier shellac ink on top of the dry oil-based ink. With a large brayer, I laid down vertical strokes until the ink ran dry and finished the piece with spare lines to unify the composition.”

A retired speech-language pathologist of forty years, Gin often used art and literature when instructing her young students. Once retired, she began taking art courses at Clatsop Community College in Astoria and studied under acclaimed artist Royal Nebbeker who got her started in printmaking. “I think I’ve been drawn to the same things my whole life: color and texture,” says Laughery. As inspiration for her prints, the artist reports, “My husband and I love to take road trips, our last through Arizona. We like to hike. All those visual memories come together over time. I wake up thinking about them, processing them. I take photographs and look at images in preparation for a print, but I don’t copy them. I review them and then put them away to allow my imagination to take over. I rarely make sketches beforehand since the press somewhat dictates what happens. None of my work is based on a specific site; it’s about a feeling, a memory.” Now living near Dry Canyon in Redmond, Laughery states, “I like the bones of our landscape here, the repetition of pattern, the geological stratification, the subtlety. I really want people that like my art to be able to find something new each time they look at it. In this sense it would never be static.”

To view Gin’s exquisite prints in person, visit the Hood Avenue Art Gallery in Sisters or the Imogen Gallery in Astoria. You can also view her website at ginlaughery.com