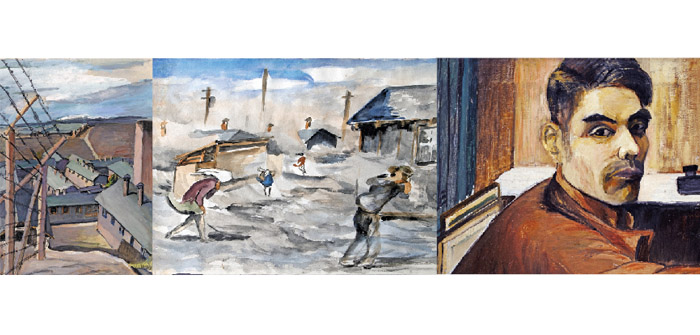

(Minidoka Barbed Wire, Minidoka Sandstorm and Self Portrait by Takuichi Fujii)

In 1936, Seattle resident and rising artist Takuichi Fujii was among ten artists chosen to represent Washington state at the First National Exhibition of American Art in New York. Six years later, the Japanese-American artist and his family were torn from their home under Executive Order 9066 and spent three and a half years imprisoned in a remote High Desert camp. During those years, Fujii continued his artistic practice, documenting the stark conditions of daily life.

After being stored away by the Fujii family for nearly half a century, this important artwork sharing the story of Japanese-Americans during World War II is now coming to the High Desert Museum.

Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii will open at the Museum on Saturday, October 19. The exhibit has been called “the most remarkable document created by a Japanese-American prisoner during the wartime” by distinguished historian Roger Daniels, Charles Phelps Taft Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Cincinnati.

“This will be the first time the exhibit has been viewed in Oregon,” said Museum Executive Director Dana Whitelaw, Ph.D. “We are honored to show this important work, help tell the story of the Fujii family, and reflect on and learn from this part of American history.”

During World War II, the U.S. government imprisoned without charge 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, approximately two-thirds of whom were United States citizens. The government used racist propaganda and fear-based arguments to justify their actions. For those who were incarcerated, the experience was life-changing.

Fujii (1891-1964) left Japan in 1906 to make his home in Seattle, where he established a business, started a family and began his artistic practice. By the 1930s, he had become a well-recognized artist for his American realist style with attention to modernist currents. After war broke out between the United States and Japan, Fujii and his family were forced from their home, taken to a temporary detention center in Puyallup, Washington and then was moved to the isolated Minidoka Relocation Center in the High Desert of southcentral Idaho.

Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii documents the artist’s perspective of the camp, contrasting with the U.S. government’s sanitized versions of the era. During this time, he painted with oil and watercolors and sculpted. He also kept an illustrated diary. Nearly 400 pages in length, it chronicled his family’s forced removal from Seattle and concluded with the closing of Minidoka.

“Fujii’s works illuminate the bleakness of everyday life in confinement as well as moments of beauty and hope,” said Museum Senior Curator of Western History Laura Ferguson, Ph.D. “For some of those incarcerated, art served as a means of expression and survival. Fujii’s work makes apparent the resilience of those imprisoned.”

After the war, Fujii and his family moved to Utah and then on to Chicago as part of the government’s resettlement program. Fujii’s artwork from the period was kept in storage by his family. After his death, his grandson recognized its significance and began translating the diary.

Witness to Wartime: The Painted Diary of Takuichi Fujii (highdesertmuseum.org/witness-to-wartime) will be on display through January 5, 2020.

The exhibit is curated by Barbara Johns, Ph.D., and organized by Curatorial Assistance Traveling Exhibitions, Pasadena, California. It is made possible by Central Oregon Daily with support from 1859 Oregon’s Magazine – Statehood Media, Cascade A&E and the James F. and Marion L. Miller Foundation.